Felicia Sanders’ job is for the birds. Literally.

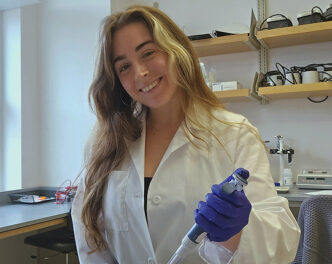

Sanders, who holds a master’s degree in biology from Clemson University’s Department of Biological Sciences, leads the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources’ Coastal Bird Conservation Project.

While there are many birds at the coast, including bald eagles, swallow-tailed kites, and osprey, the internationally recognized project focuses on shorebirds and seabirds.

“That’s because they’re really in trouble, and they’re declining fast,” said Sanders, who has worked for the DNR since 2001. “These shorebirds are in trouble, partly because they’re just strictly coastal during most of the year. Everybody, including me, wants to be at the coast, so there’s limited habitat where shorebirds can live undisturbed.”

It’s not just coastal development that threatens these birds. Wealth has, too, according to Sanders.

“More people have boats and GPS units, so they can navigate to and recreate on remote sand bars where the birds are just resting. Technology and affordability of boats have exponentially caused the disturbance,” she said.

This makes protecting and conserving this habitat even more crucial, considering that two-thirds of all shorebird species in North America nest in arctic and boreal regions. Each spring, vast waves of birds that winter as far south as South America stop in South Carolina to refuel on their migration north.

Last stop

Spring, especially April and May, is important. Some shorebirds migrate 18,000 miles each year and Sanders’ research shows South Carolina is the last stop on their northern migration to Arctic nesting grounds.

“That makes protecting and conserving habitat in South Carolina even more critical,” said Sanders, who was named the 2020 Biologist of the Year by the Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

Sanders has helped establish partnerships with private, government and non-profit entities and galvanized grassroots support to protect coastal bird habitat at about 30 sites. Her accomplishments include the designation of five coastal island Seabird Sanctuaries, allowing beach closures to increase nesting success and the Cape Romain-Santee Delta Region’s designation as a Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network Site of International Importance.

“South Carolina can be proud of a long legacy of conservation,” she said. “The preserved lands are one reason so many coastal birds live and stop on our shores.”

Sanders has spent three decades on conservation efforts for a wide diversity of bird species, including sea, shore and wading birds and also red-cockaded woodpeckers, grassland birds and neotropical migrants.

Making a difference

After completing her undergraduate studies at Duke University, Sanders spent about a dozen years working temporary technician bird jobs. But she decided she wanted to lead a project and make a difference. She knew she had to get a master’s degree to do that.

“I absolutely love Clemson. It gave me exactly what I wanted,” she said.

Sanders wanted to learn statistics so she could be a scientist. She wanted to learn to write professionally, and she wanted to design a research project.

She accomplished them all, and she was ready and qualified for the job she now holds.

“I use skills I learned during my master’s almost every day,” she said. “I think it’s really rare that somebody goes to grad school with that specific of a goal in mind. I use almost every class in my daily work.”

Collaborative effort

Over the past 10 years, Sanders has partnered with Patrick Jodice, a wildlife research biologist with the South Carolina Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and professor in the College of Agriculture, Forestry and Life Science’s Department of Forestry and Environmental Conservation, on collaborative graduate student research projects. The projects answer questions that help DNR better manage beach-nesting birds. Two of those graduate students now work for DNR.

While Sanders loves research, she realized that outreach and environmental education are equally important for conserving the shorebirds.

“Environmental education is one of our focuses right now. If the next time people are at the beach and they know these birds are just stopping here on a hemispheric long journey, maybe they’ll stay back and just watch the birds, not disturb them. Maybe they’ll realize that the beach is the home of some of these animals and not just a place to play,” she said. “I not only work on shorebirds because there’s a need, but because I have really just fallen in love with them.”