This story was written by Katie Gerbasich, a senior sports communication student, as part of a project with the Robert H. Brooks Sports Science Institute.

Take a nylon webbed football belt, loop a resistance band through it and tape it down to the bottom of a football cleat. This was one of the initial ideas of Clemson Athletics’ team orthopedic lead, Dr. Steve Martin, for a hamstring rehabilitation device.

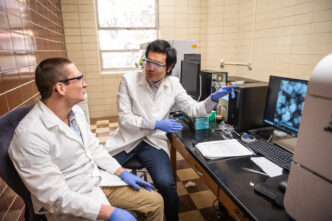

A graduate student in the Department of Bioengineering, Quinn Castner, has spent the past year and a half refining this novel idea under the direction of Reed Gurchiek, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Department of Bioengineering, through the Human Movement Biomechanics Lab (HuMBL).

The team received research funding from Clemson University’s Robert H. Brooks Sports Science Institute in 2024 to develop a passive assistive hamstring device. They aim to support the muscle recovery process.

The main component of the device is an elastic band that spans two joints, providing passive knee torque. When an athlete wears it, the elastic band offloads some of the hamstring muscle activity. It is highly modifiable, with approximately six different parameters that clinicians can adjust to create a customizable assistance profile.

“As athletes are going through the rehab process, we’ll start them off with the stiffest band that’s going to help them the most,” Castner said. “As they progress, clinicians can recommend bringing them down to a less stiff band, until ultimately, they won’t need to use it at all.”

Hamstring injuries are currently the most prevalent time-loss injury in field-based sports. As a Clemson Football athlete, Castner has witnessed many of his teammates being sidelined due to muscle tears. Athletes who have previously torn their hamstrings are at a higher risk of tearing it again.

“The plaguing of hamstring reinjuries keeps these athletes out for weeks or months,” Castner said. “It’s unfortunate to see. Especially the fact that there’s really not much of an answer to help this rehabilitation process to give these players a longer or better career.”

Standard rehabilitation protocols typically entail reducing sprinting to allow the muscle time to heal.

“If you’re an athlete and sprinting is a part of your sport, it’s not good for you to go weeks without running,” Gurchiek said. “It’s not good for your cardiovascular or neuromuscular health. So the ideal scenario would be for the clinician to allow you to run, but to control how much load is imposed on the hamstrings.”

Before coming to Clemson, Gurchiek studied human movement biomechanics and hamstring injuries at Stanford University as a postdoctoral fellow in the Wu Tsai Human Performance Alliance, focusing on bioengineering.

A combination of empirical and simulation-based methods has guided this research. The team wanted to ensure that the device did not hinder the athlete’s natural running pattern. In an overground study, subjects ran 40-yard sprints on a field with and without the device to compare results.

“Across the testing conditions, there wasn’t more than a 1 to 3 percent difference between wearing the device and not wearing the device,” Castner said. “Which we’ve deemed, as such a small percentage, that it’s most likely insignificant.”

In a second study, the team sought to measure the extent to which the device actually offloads the hamstring muscle. Measuring the force produced in a muscle is challenging.

The team’s solution was to use electromyography (EMG) sensors to record muscle activity.

“The muscle activity measure that we’re getting doesn’t linearly translate to muscle force, but it acts as a surrogate measure,” Gurchiek said. “Estimates of muscle force ultimately require simulation techniques.”

To produce these simulations, Gurchiek and Castner combined knowledge about the physiology of muscles, tendons and the motion of the runner to create a computer model.

“In the future, we’ll use a model of the person along with the EMG data and simulation techniques to estimate how much force is going through the muscle,” Gurchiek said.

So far, the device has shown promise in its ability to provide rehabilitative assistance. The team has kept Dr. Martin involved by sharing feedback about data and design features. Now, they’re looking towards getting it into the field.

“Once we have devices that are clean and can be worn by actual athletes in practice, that’s the next step — putting it to work in actual rehabs and practices,” Castner said.