Two Clemson University civil engineers said their newly published research is the most comprehensive analysis so far of what causes flash drought, a weather phenomenon that has been blamed for billions of dollars in crop damage and increased wildfire risk.

Former Clemson Research Assistant Sourav Mukherjee and his advisor, Associate Professor Ashok Mishra, said their work could lay the groundwork for additional research that helps predict future flash droughts so that measures could be taken to prevent or alleviate the effects.

As part of their work, they came up with a novel way of identifying the globe’s flash-drought “hot spots,” which include most of the Eastern and Central United States and a swath of the coast in the Pacific Northwest.

“This information could be used to develop a forecasting model in the near future,” Mishra said. “We can use the information from hot spots to help identify the most important precursors for flash drought.”

Mukherjee and Mishra reported their findings in a recent edition of Geophysical Research Letters, adding their voices to a flood of new research aimed at identifying, characterizing and predicting flash droughts.

While standard droughts evolve slowly over months or years, flash droughts intensify quickly, sometimes in as little as a few days, with potentially disastrous results.

For example, the 2017 flash drought in North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana and Canada was the worst to hit the Northern Plains in decades, causing extensive agricultural damage and losses totaling $2.6 billion in the United States alone, according to the National Integrated Drought Information System.

Mukherjee and Mishra focused their research on the period from 1980-2018 and obtained their data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis.

As part of the research, they created a way of measuring how hard each of the world’s 26 climate divisions have been hit by flash drought during the period they studied. The analysis took into account the number of flash-drought events, mean severity and average rate of intensification as measured by depleted soil moisture.

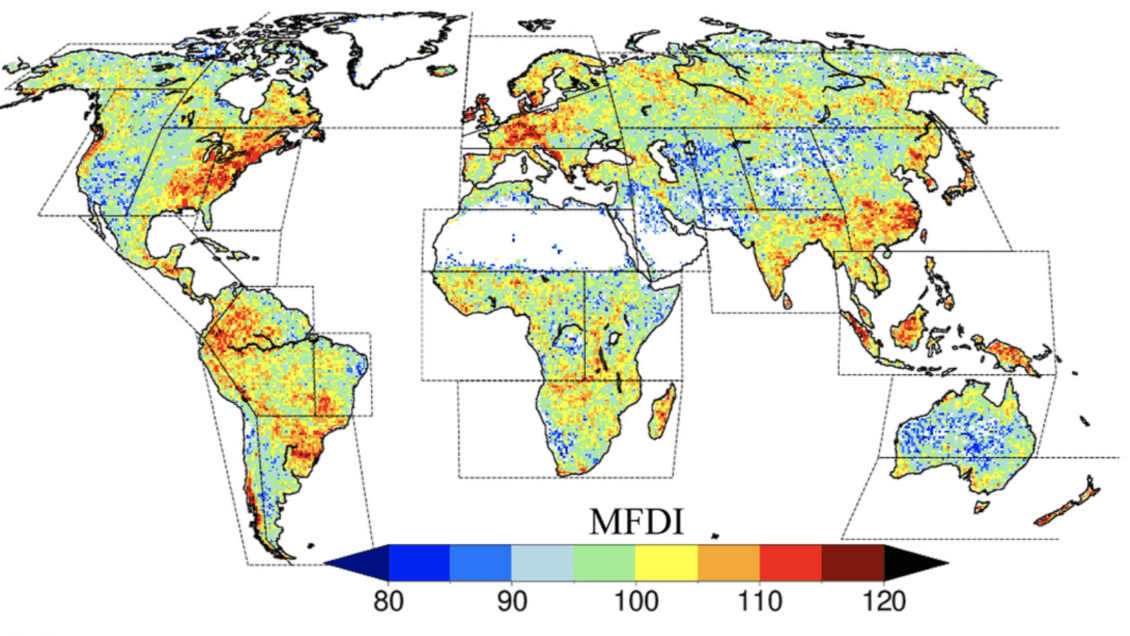

The result was the Multivariate Flash Drought Indicator, or MFDI, which boils down the potential impact of flash drought to a single number for each location.

“Previous research on flash drought has picked up one characteristic and assessed the risk based on that,” Mukherjee said. “However, we think that it should be a multivariate approach, which combines several characteristics together. And that is what is unique about this paper– that we have combined three characteristics into a multivariate index of flash drought.”

The mean MFDI was 100, and any location that registered higher was considered a hot spot. Understanding where hot spots have been in recent decades could help predict where they will be in the future, Mukherjee said.

The study results suggest potential hot spots across the majority of Central and Eastern North America; the Amazon basin; Southern and Western South America; Southern, Southeastern and Eastern Asia and Central and Northern Europe, the researchers wrote.

Also as part of their research, Mukherjee and Mishra sought to better understand how flash drought evolves. They analyzed several climate variables, including precipitation, daily minimum and maximum temperature, surface pressure, actual evaporation, potential evaporation, vapor pressure deficit, root-zone soil moisture and soil-moisture coupling.

“Our results indicate that precipitation is the primary driver of FD evolution, while the effect of temperature, vapor pressure deficit, and land-climate interaction varies across the climate divisions after the onset of the events,” they wrote in the paper’s abstract, using an abbreviation for flash drought.

The paper’s title is, “A Multivariate Flash Drought Indicator for Identifying Global Hotspots and Associated Climate Controls.”

Mukherjee studied under Mishra, received his Ph.D. from Clemson in August 2021 and then continued at the University as research assistant during the flash-drought research. He is now a postdoctoral researcher with the U.S. Forest Service.

Jesus M. de la Garza, chair of the Glenn Department of Civil Engineering, congratulated Mukherjee and Mishra on publishing the research.

“Their novel work adds to a growing body of flash-drought research, a crucial step toward finding sustainable solutions,” de la Garza said. “Their paper not only adds to knowledge in the field but also helps boost Clemson’s international reputation for high-quality research. Their success is well deserved.”

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu