Heidi Zinzow, Clemson University

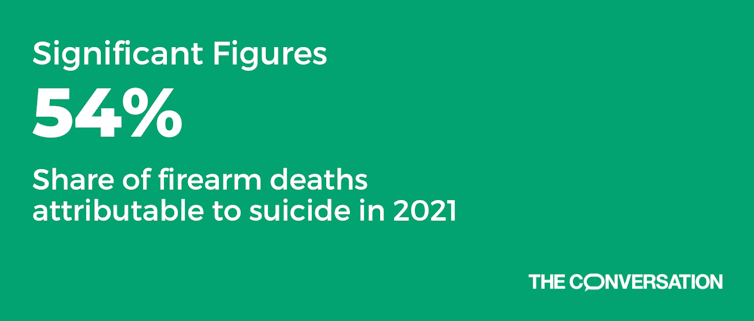

More than half – 54% – of all firearm deaths in the United States in 2021 were attributable to suicide, according to February 2023 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Suicide deaths involving firearms – the most common means of suicide in the U.S. – have increased 28% since 2012. Groups particularly at risk include men and veterans, who are more likely to have access to and experience with firearms. Research also suggests that alcohol use is a significant risk factor for gun-related suicides, as opposed to suicides involving less lethal means. This is particularly true for young adults and middle-aged people.

Access to firearms is a key risk factor for suicide due to their high lethality. Suicide attempts that involve firearms end in death 90% of the time. Suicide is often an impulsive act, and when a person has access to swift and lethal means such as a firearm, there is limited opportunity to intervene or allow for a suicidal impulse to pass.

It is a common myth that once a person has made up their mind to die by suicide it is not possible to prevent them from doing so. In fact, most individuals who survive an attempt do not attempt suicide again, and those who survive an initial attempt using one method are unlikely to switch to a different method.

These findings underscore the importance of restriction of access to firearms as a critical suicide prevention strategy.

Research indicates that storing a firearm safely reduces the risk of the owner – as well as others, including any children living in the home – dying by suicide.

Firearm safety measures include gun safes, lockboxes, storing firearms separate from ammunition, and either voluntarily or involuntarily removing firearms from the home when a person has a mental health condition or other warning signs for suicide risk.

Nineteen states – California, Connecticut, Florida and Maryland among them – as well as the District of Columbia have enacted so-called red flag laws. These allow law enforcement, family members and sometimes school administrators or health care professionals to petition the court to remove a firearm from the home of a person at risk of harming themselves or others.

In addition to these measures, policymakers and care providers can address other risk factors for suicide as part of a comprehensive suicide prevention strategy. This includes screening and identifying people who are at high risk, treating underlying mental health conditions, improving access to mental health care and encouraging stronger family and community connections. Prevention priorities also include reducing risk factors such as exposure to violence, financial strain and chronic illness.

Another strategy is training friends, teachers, clergy, coaches and other community members in assessing suicide risk and referring individuals to resources. This has been shown to increase both the likelihood that a trained helper offers needed assistance, as well as the likelihood that the person who is suffering seeks help.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call 988 to speak with a trained listener. Veterans can press 1 after dialing 988 to connect directly to the Veterans Crisis Lifeline. Or, text HELLO to 741741. Both services are free, available 24/7, and confidential.

Heidi Zinzow, Professor of Psychology, Clemson University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.