Clemson University organic chemist Byoungmoo (Boni) Kim wants to transform the way chemists build the essential molecular structures behind modern medicines.

Kim is working to create a versatile “toolbox” of reactions that allow scientists to quickly build complex molecules from simple, stable starting materials — such as alcohols and carboxylic acids.

He likens the work to using simple individual Lego® bricks to construct elaborate structures such as buildings, cars and characters.

“It’s like that with molecules. You can take simple building blocks and through synthetic methods, you can generate various items, including many pharmaceutical compounds. These therapeutic drugs can save lives, but they need organic chemistry to make them happen,” said Kim, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry.

Kim has received a five-year $1.88 million National Institutes of Health MIRA (Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award) grant for the research. MIRAs fund investigators and their general research ideas instead of a narrow set of specific research aims. The grants permit investigators to be flexible in their research, allowing them to explore new directions from their original proposals based on their discoveries.

Slow and cumbersome

The challenge is that traditional methods for turning these basic molecules into new medicines are slow and cumbersome. Chemists often need multiple chemical steps and transformations to convert the simple molecules into something more complex.

“It’s like building a car hand-by-hand, piece-by-piece rather than relying on an assembly line,” Kim said.

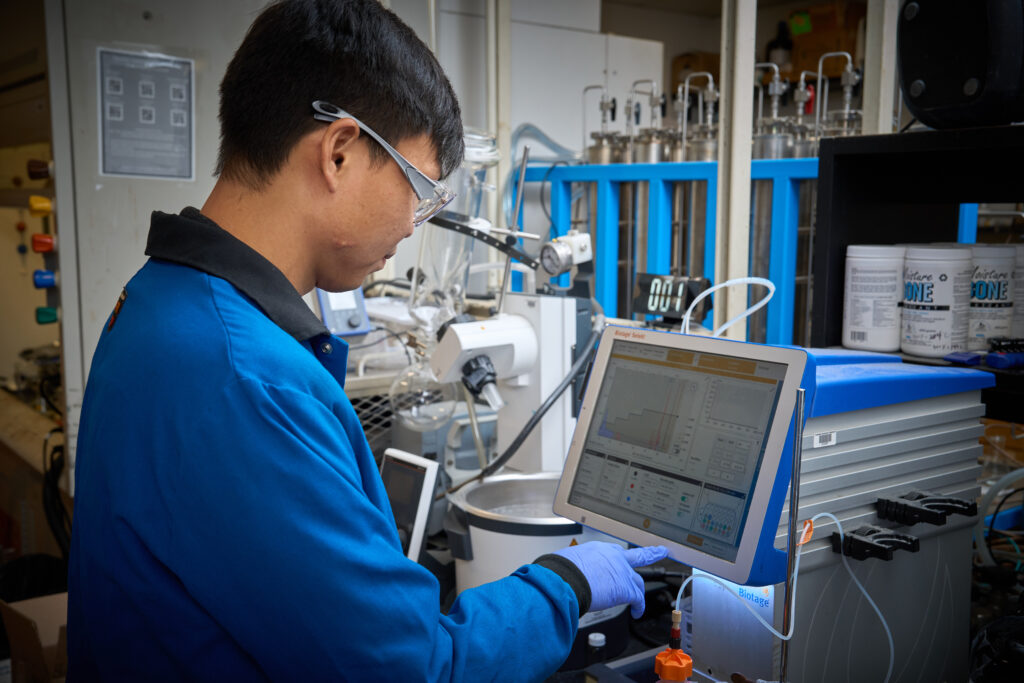

Kim’s research group will use multi-function reagents and catalysts to streamline the process, making it possible to create diverse, biologically active molecules in fewer steps and with greater precision.

The researchers will employ sulfonyl fluoride reagents to activate the typically tough carbon-oxygen chemical bonds in alcohols and carboxylic acids, opening them up to join with diverse partners — amines, fluorinated segments and other valuable motifs — all in one step. By using versatile base metals to direct the reactions, the team can control the 3D shape, or stereochemistry, of the products, which is a crucial feature for effective drugs.

Readily available

“Our approach is all about starting with sustainable molecules like alcohols and carboxylic acids, which are readily available in nature and industry. They are cheap and safe and also minimize the environmental impact of the research and manufacturing process,” Kim said.

Kim said he’s not targeting one specific disease with the research but instead is building the tools that allow researchers to make a vast variety of molecules.

“If you have a hammer, you can build certain things. You could use a nail and make things out of wood. But if you can expand your toolbox — pliers, screwdrivers and wrenches — you can make almost anything,” he said. “This is foundational work. We’re building the tools that could one day lead to breakthroughs across many areas of medicine by giving other scientists a set of robust, reproducible tools they can use to accelerate their own research.”

Kim said he eventually wants to target specific diseases and perhaps discover new antibiotics.