Barcodes help stores track the flow of goods from the shelves to the cash register, but now Clemson University researchers are taking that concept to another level– and it could help unveil the secrets of life.

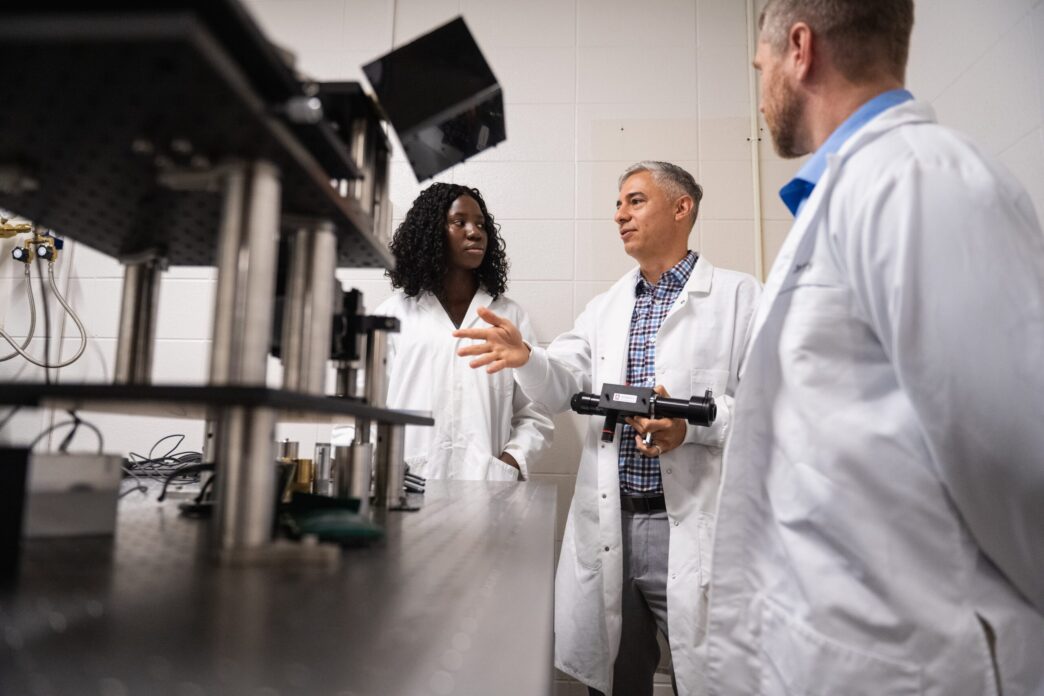

Researchers from two of Clemson’s colleges are teaming up to create tiny tags made from DNA and fluorescent dyes that light up in unique patterns like barcodes. The barcodes would help researchers track specific proteins in cells, offering a deeper view into how those cells behave, interact and change.

With that information, researchers at Clemson and beyond would be better equipped to understand disease, map tissues and study how cells and microbes interact, all in far greater detail than before.

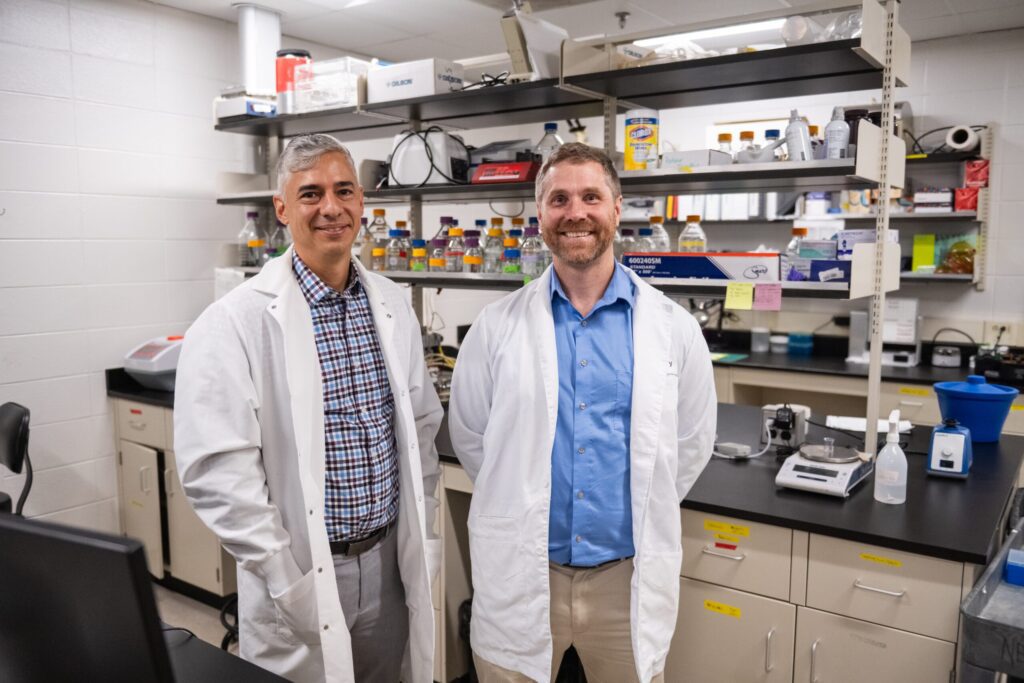

The barcode research is funded by the National Science Foundation, with Marc Birtwistle serving as principal investigator and Hugo Sanabria as co-principal investigator.

“Biology is limited by the number of things we can measure at a single time, and what we’re trying to do is increase that amount by about 10 fold so we can learn far more about both regular, normal biology, but also about disease,” said Birtwistle, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering and bioengineering.

Sanabria, a professor of physics and astronomy, likened the barcode project to creating a new way of taking a detailed census of cells inside tissue.

“The more we can see, the better we can understand how cells work, how they interact and how things go wrong in disease,” he said. “It’s like going from a blurry snapshot to a high-resolution map– it gives us a much clearer picture of what’s really happening inside.”

The team is working to create a set of about 200 glowing DNA “barcodes,” each with a unique light signature.

The barcodes are made by attaching fluorescent dyes to strands of DNA through solid-phase synthesis. Those DNA strands are then linked to antibodies, which bind to specific proteins or cell types.

Special instruments read the barcodes’ light patterns, helping scientists understand what is in a sample and how its parts are working together.

Oluwaferanmi Ogunleye, a chemistry Ph.D. candidate in the Birtwistle lab, said it is amazing how much information the team can glean from just a small sample.

“We’re using a few fluorescent tags to uncover 10 times more detail, and that has huge potential for improving how diseases are diagnosed and treated,” she said.

Current technology allows researchers to track only about 40 different features in a single sample. Clemson’s team aims to push that number to 200, opening the door to discoveries that weren’t previously possible.

Birtwistle is a faculty member in the College of Engineering, Computing and Applied Sciences. Sanabria is a faculty member in the College of Science.

“Science doesn’t care about institutional boundaries,” Birtwistle said. “This project came together because two researchers had a shared idea and complementary expertise. I couldn’t have done this without finding Hugo.”

Here is what departmental leadership had to say about the project:

David Bruce, chair of the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering:

“This kind of work is a perfect example of how Clemson researchers are pushing the limits of what’s possible. By combining engineering, chemistry and biology, they’re opening the door to discoveries we couldn’t even imagine a few years ago.”

Delphine Dean, chair of the Department of Bioengineering:

“This research shows the power of innovation at the intersection of disciplines. The tools they’re developing could change the way we study everything from cancer to the microbiome– and it’s happening right here at Clemson.”

Chad Sosolik, chair of the Department of Physics and Astronomy:

“What’s exciting is how this project brings together physics, biology, and cutting-edge technology. It’s a great example of how fundamental science can drive practical breakthroughs with real-world impact.”