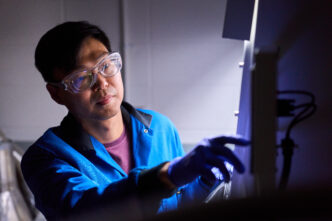

Adriana Bankston is making an impact in scientific research, but she doesn’t work in a lab.

Bankston, who graduated from Clemson University in 2005 with a degree in biological sciences before receiving her doctorate in biochemistry, cell and developmental biology from Emory University, advocates for science and innovation at the federal level.

“Scientific research is a big component of what drives this country forward,” she said.

During her career, Bankston has pushed for steady and predictable federal research funding, fought for improved professional development and training of graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, and provided evidence-based scientific expertise to help shape legislation and policy. She has worked for a university system, several nonprofits and scientific associations.

Beginning in September, Bankston will spend a year as the inaugural American Association for the Advancement of Science/American Society of Gene & Cell Therapy Congressional Policy Fellow. In that role, she will provide high-quality, science-based, independent guidance to federal policymakers.

“In my previous roles, I was trying to persuade from the outside. With this fellowship, I’ll gain an understanding of how the federal government works from the inside so I can better support the scientific research endeavor in the future,” she said.

Change of plans

Bankston had planned a career in academia. Both of her parents are faculty members in the Clemson Department of Bioengineering.

“I grew up around academia, so I was interested in being a faculty myself. That is really all I knew at the time as a career path,” said Bankston, who immigrated with her parents from Romania. She said her time at Clemson solidified her interest in science and research. “Clemson gave me an appreciation for education in this country and what can be achieved.”

After graduating from Clemson, Bankston attended Emory. There, she first worked in a lab that studied skeletal muscle biology. She then moved to another lab that did more translational research, using cell culture and mouse models to try to develop therapeutics for muscular dystrophy.

Wanted to do something good

“I wanted to do something that would help patients and think about cures for the disease. I wanted to do something good with my research,” said Bankston.

Bankston went to the University of Louisville for her postdoctoral fellowship. It was there that she began questioning her career choice.

The first principal investigator she worked for in Kentucky had a grant run out after two years, forcing her to switch labs. Seeing PIs struggle to find funding for their labs caused Bankston to start looking for other ways in which she could use her degrees to advance research.

“I realized how much responsibility PIs have to their trainees,” she said. “I moved from Georgia to Kentucky for this opportunity and then there was no more grant money. What now?”

She went to the school’s postdoc office to see what career resources were available. She didn’t find much. But she got involved with the postdoc office and helped start a career seminar series that brought in speakers to talk about their careers. She then continued working with the National Postdoctoral Association.

Away from the bench

Bankston said that experience gave her an idea that she could support research away from the bench.

Throughout her career, she advocated for steady, predictable federal funding for the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health. She has pushed for reducing administrative burdens on academic investigators. She has educated Congressional leaders on the importance of graduate students and postdoctoral researchers to the research enterprise. She drafted a STEM pipeline amendment which was included in the CHIPS (Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors) and Science Act that was signed into law by President Joe Biden in August 2022.

She has now transitioned into working more directly with the legislative branch.

“Those who are writing the law rely on the expertise of the scientific community so they can develop the best possible policy,” she said.

Bankston doesn’t yet know which Congressional office or committee she’ll be working with starting in September, but she is eager to apply her scientific knowledge and passion for research funding and training to federal policymaking.

“I’m looking forward to contributing to our nation’s advancement in science and technology in this way,” she said. “As an advocate and Congressional staffer, I can have a bigger impact on scientific research than if I had stayed on the bench.”