Since its founding, Clemson University has been photographed thousands of times, in every season from nearly every angle. A new project from CCIT’s Clemson Center for Geospatial Technologies has raised the bar for campus imagery, however, using drones and high performance computing to process more than 7,000 high-resolution aerial photos as part of an inter-department collaboration.

“This has been a game changer in terms of collaboration to eliminate data redundancy and lower costs,” said Patricia Carbajales-Dale, executive director of the Center. “Clemson is a high pace, dynamic campus where changes to the built environment happen almost daily. Being able to capture high resolution data at a fraction of the cost that normally takes while ensuring the highest quality is key for our campus operations.”

Collaborating across campus

Departments across Clemson have explored the benefits of drone imagery for the last several years. The Center boasts a wealth of experience flying unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV) to collect a variety of information, including a yearly campus mapping project. With many at the University feeling financial and logistical effects from COVID-19, the Center’s staff reached out across campus to collaborate on its drone photography project and share the results. More than eight departments, including athletics, facilities, engineering and others, responded enthusiastically and agreed to contribute.

“Being able to partner with other university resources is helpful so that we aren’t hiring our own drone imagery provider,” said Jason Taylor, associate director of IPTAY. “Also having consistency in our imagery between the university facilities and athletic facilities departments is helpful for everyone to stay on the same page as we grow and manage that growth appropriately.”

A detailed aerial view of campus offers a wealth of possibilities. Facilities can see what areas need maintenance, athletics can visualize game day parking and pedestrian management, and academic departments can use the map for valuable research and historical data.

“Figuring out where we can park up to 25,000 cars on this campus has become affectionately known as ‘scratchin’,” said Taylor. “With these images, we can now do high tech ‘scratchin.'”

Over the course of 12 days last December, UAV and LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) specialist Maziar Mahani took advantage of the quiet campus—and lack of leaves on trees—to snap 7,219 images for the project. He began at 9 a.m. and completed three or four flights each day.

The power of Palmetto

Once Mahani photographed every part of campus, he faced a new problem: how to process and aggregate all 7,000 images together efficiently. He didn’t have to look far for his answer, as Clemson’s Palmetto Cluster supercomputer fit the bill perfectly. Mahani worked with CCIT’s Cyberinfrastructure Technology Integration Advanced Computing/Research Facilitation team to learn the software and programming necessary to develop a workflow on one of the country’s most powerful supercomputers.

The team installed specialized geospatial processing software on the Palmetto Cluster, one of the world’s TOP500 fastest supercomputers and of the country’s top five among public universities. Using more than 130 nodes equipped with a state-of-the-art NVIDIA graphics processing unit, Palmetto greatly accelerated Mahani’s production timeline.

“It really helped by reducing the amount of processing time,” Mahani said. “It would have taken a month on a personal computer, but on Palmetto it took seven or eight hours. Without high performance computing, I’d probably still be processing.”

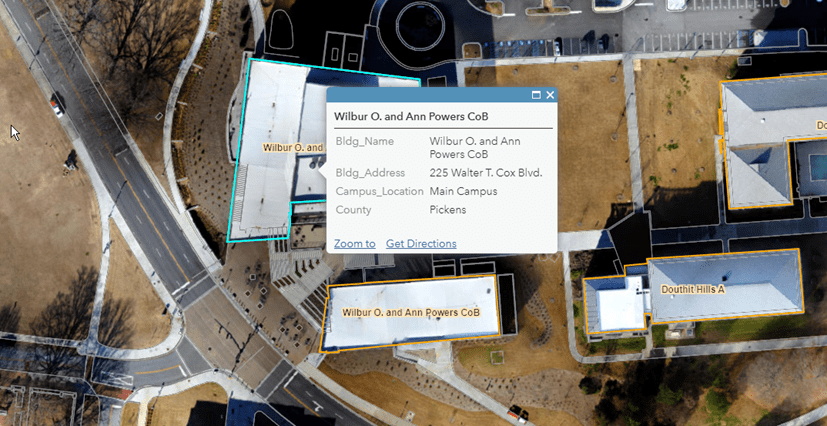

The results were stunning. With the power of Palmetto, Mahani stitched the photos together over a basemap of campus to create an extremely detailed, up-to-date image of Clemson at six times the fidelity of Google imagery—to the level of being able to read individual parking space numbers.

“We love it,” said Ward Mitchell, GIS manager for University Facilities. “The collaborative effort is fantastic and it’s a great benefit to the university.”

Mitchell uses the imagery with the department’s basemap, allowing him to layer useful information over the detailed photos. With 5,000 manhole covers, 3,500 light poles and miles of road, the ability to see exactly what needs attention from afar is invaluable.

The project provides safety benefits for facilities and the public, Mitchell said. Road crews can check for cracks or obscured manhole covers without venturing into a busy street, and future apps will allow users to report broken sidewalks and potholes. Mahani’s images also revealed where water may puddle on rooftops, as well.

“People might just see a picture, but I see a lot more,” said Mitchell. “There’s a ton of information here.”

The Center plans to continue working with various departments to create GIS data about and for Clemson. In April, Mahari worked with Drs. Jennifer Ogle and Christopher Post to fly a drone collecting LiDAR information, which can be used to measure distance and create an accurate 3D model of campus.

“We hope to expand this model to include other geospatial assets owned by Clemson where we can collectively acquire, store, and distribute geospatial data needed by many departments on campus,” said Carbajales-Dale.