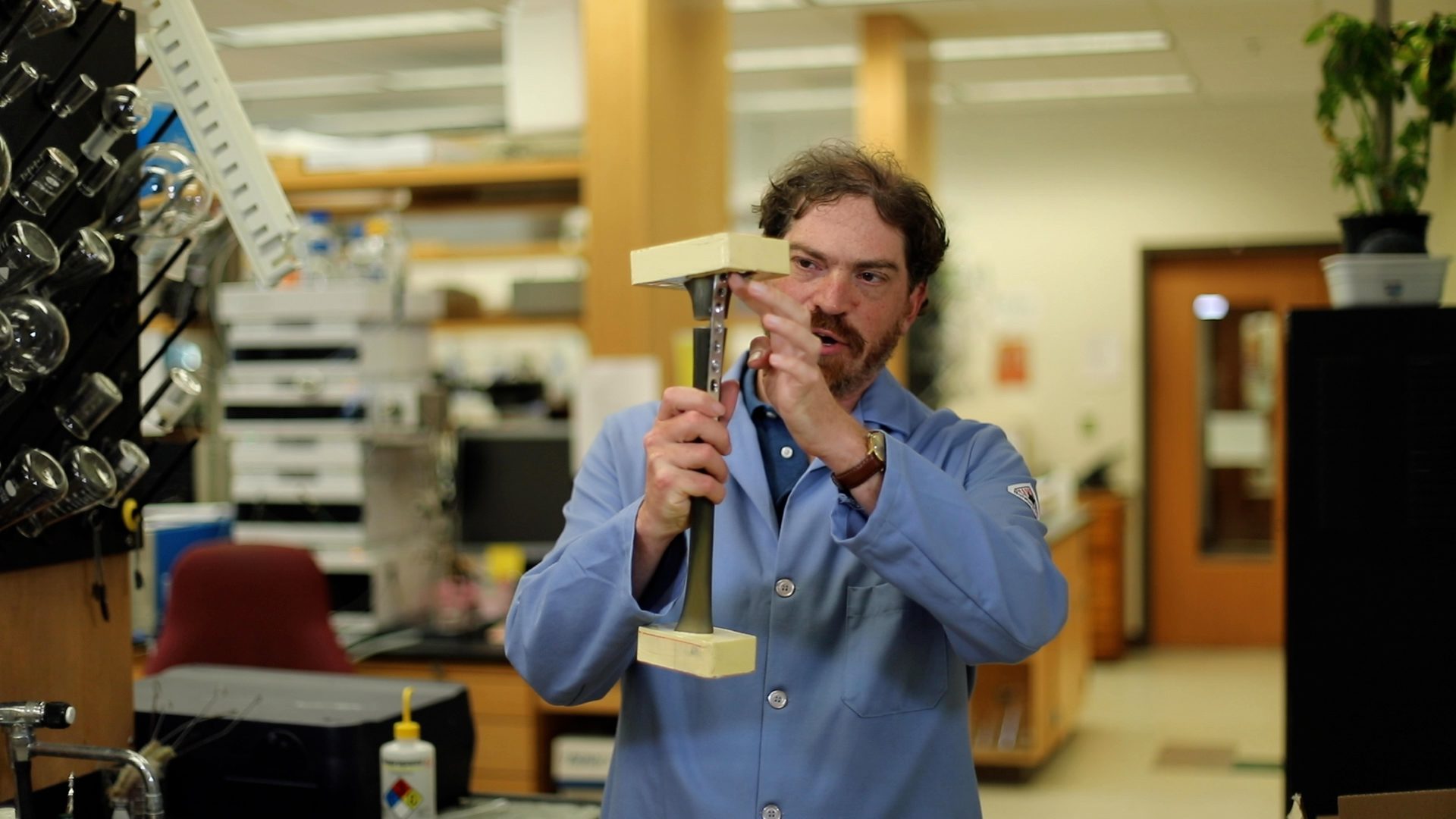

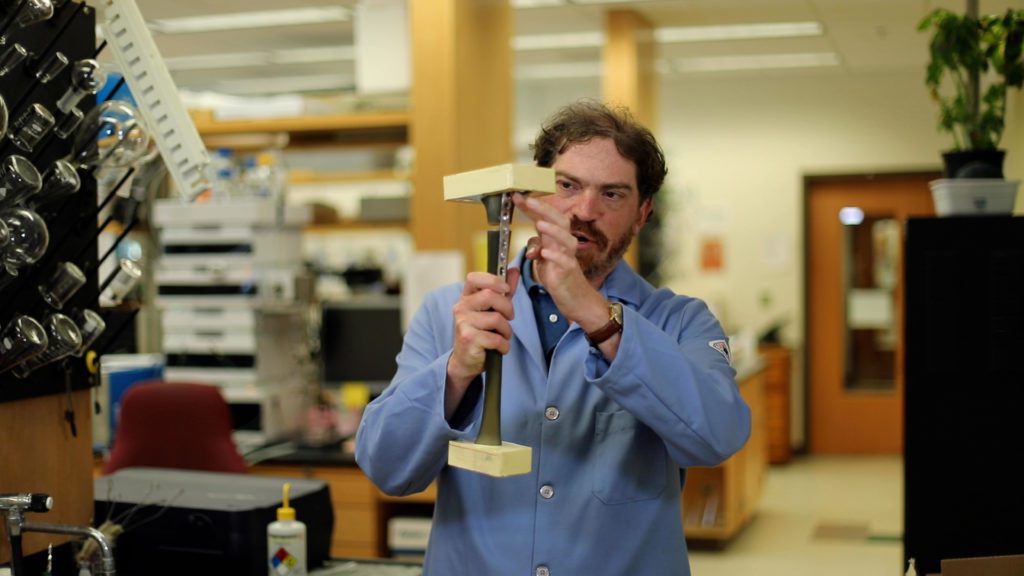

Jeff Anker has always liked to tinker.

“I like to play with things and see what happens,” said Anker, a chemistry and bioengineering professor at Clemson University, who spent six months in Finland as a part of the Fulbright U.S. Scholar program. “It’s why I became a researcher.”

Anker had a chance to “tinker” at Finland’s Tampere University, where he collaborated with researchers to try to come up with a material that could replace bone in people who have lost a section of bone because of a traumatic injury or bone cancer.

“We want to be able to make materials that can replace bone without having to harvest bone from other parts of the body. It would be a game-changer,” said Anker, who was in Finland from July to December.

Two Tampere University professors with Clemson ties hosted Anker while he was in Finland.

Jonathan Massera earned his Ph.D. in Materials Science and Engineering (MSE) from Clemson and focuses his research on bone scaffolds. Bone scaffolds are 3D biomaterial structures that support bone healing. Laeticia Petit, previously a research assistant professor at Clemson for three years, specializes in biophotonics and making fiber-based sensors.

When a person has a traumatic injury or bone cancer and when resected, the bone must be replaced.

“If the bone loss is in your jaw, it affects your looks and ability to talk and swallow. It’s a huge issue,” Anker said. “Currently, doctors take a piece of bone from another part of your body, sculpt it, put it in and hope things heal properly. It would be great if doctors could 3D print the bone you needed.”

Big problem

The problem comes when trying to replace a large piece of bone. If there’s insufficient blood to supply enough oxygen and nutrients, cells that go into the bone scaffolding will die when they reach the center. If the bone doesn’t heal correctly, it will eventually fatigue and fail.

“You can run into a lot of issues with large defects,” said Anker, whose research has focused on developing sensors that are attached to orthopedic plates used to repair unstable bone fractures. The sensors track healing and detect infection. If the fracture is too severe, bone scaffolds fill the defect and provide something to which new bone can attach.

Anker and a Tampere University student wrote computer code that changed the shape of the bone scaffold from staked log pile-like structures to something more modular that could be put together like LEGO blocks. They also made holes in the blocks large enough to accommodate screws.

“We wanted something modular that essentially allows you to combine different components, including sensors that let us know the acidity and oxygen concentrations inside the scaffold. We also wanted space where we could put screws and plates made of metal to give it more rigidity, especially for applications like mandibles, which have to take a lot of force,” he said.

Continuing to collaborate

Anker said the researchers would continue their collaboration. In addition, Anker plans to work with other researchers who use high-resolution x-ray imaging and ultrasound to determine how to incorporate the technology in bone scaffolding. Anker intends to return to Finland this summer.

A program of the U.S. State Department, the Fulbright Program provides approximately 8,000 annual fellowships to college and university faculty, students, artists and professionals from various fields. These support both visits from U.S. citizens to foreign countries and vice versa. Finland was one of the first nations offered the opportunity to join the Fulbright program and has had over 6,000 alumni since 1949. Besides research and teaching, Fulbright Scholars share knowledge and foster meaningful connections with communities in their host countries.

Anker and other Fulbright Finland Scholars from the U.S. gave a talk about the cultural differences between Finland and the U.S. For instance, Finns look at the weather differently than Americans. Things close down at the threat of snow in the southern U.S. That would be disastrous in Finland, which has snow half the year.

“They have this saying in Finland that there’s no such thing as poor weather, only poor clothes,” Anker said.

Anker’s family accompanied him to Finland and had their own cultural experiences. His two children attended the Finnish International School of Tampere and joined the Girl Scouts. His wife took a Finnish class. They went skiing for the first time and went reindeer and dog sledding.

“It was a wonderful experience,” Anker said. “It was an ideal time and opportunity to get to know people, brainstorm ideas and come up with new research. That was exciting. And I got a chance to tinker a bit. That part was really fun and reminded me why I was doing what I’m doing now.”

The College of Science pursues excellence in scientific discovery, learning and engagement that is both locally relevant and globally impactful. The life, physical and mathematical sciences converge to tackle some of tomorrow’s scientific challenges, and our faculty are preparing the next generation of leading scientists. The College of Science offers high-impact transformational experiences such as research, internships and study abroad to help prepare our graduates for top industries, graduate programs and health professions. clemson.edu/science