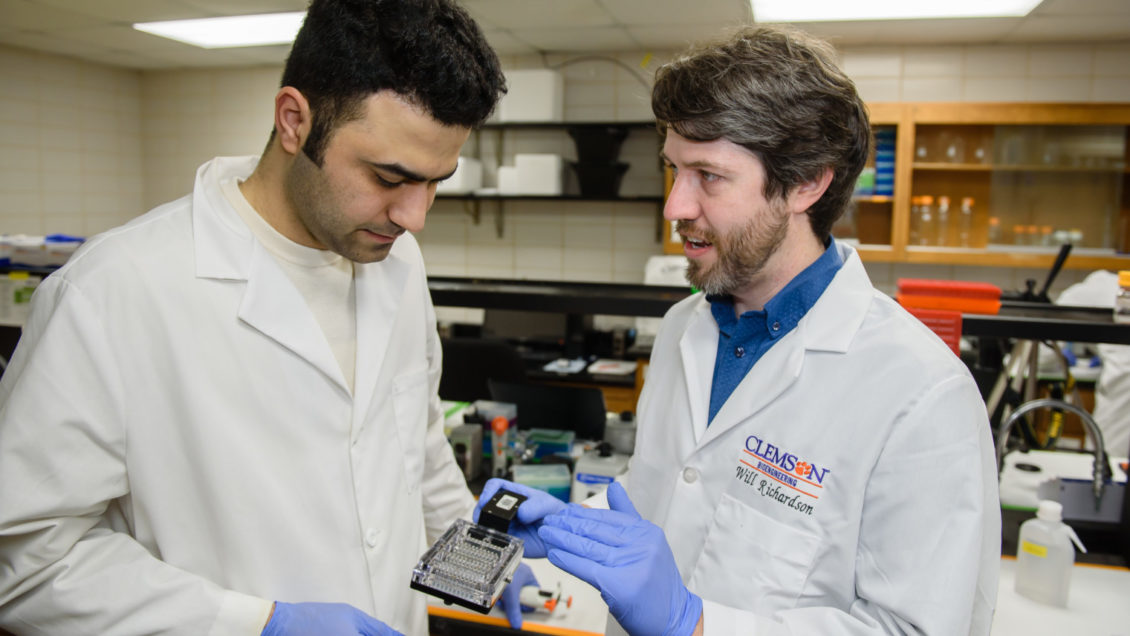

In just three short years, William Richardson has gone from a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Virginia to an assistant professor in Clemson University’s bioengineering department and a junior investigator for the South Carolina Center for Translational Research Improving Musculoskeletal Health (SC-TRIMH). And this year, he’s completed a milestone as a junior investigator: receive a major R01 grant, and he has recently graduated from the junior investigator program.

In February, Richardson received a $1.8 million-grant from the National Institutes of Health for five years of research focused on cardiac fibrosis.

“Receiving this grant affirms what I’m doing, and it’s an honor,” Richardson said. “I think as a new investigator there’s all kinds of transitions and it’s a really steep learning curve. I went from basically being in school and a student, to all of a sudden- managing students, advising graduate students, teaching courses, writing papers, writing grant proposals, serving on committees.”

He is one of five junior investigators in SC-TRIMH, which was recently established as a center in October through a COBRE grant, and he’s the second to reach his goal of receiving an R01 grant. Once a junior investigator receives a major funding grant, he or she graduates, and a new junior investigator is chosen.

Hai Yao, Director of SC-TRIMH and Ernest R. Norville Endowed Chair for CU-MUSC Bioengineering Program, said Richardson has excelled in the program.

“We are very proud of Will as he is the second of our SC TRIMH trainees to obtain major NIH funding,” Yao said. “The explicit purpose our COBRE program is to train promising junior investigators how to successfully format their research strategy and grant proposals to NIH standards. Will has successfully established himself as an independent scientist at the national level.”

Yao said an important part of the SC-TRIMH junior investigator program is the mentoring.

“While there are many investigators on campus who have great potential for biomedically related science, most need mentoring in how to form a viable research team and scope of work required for NIH funding,” Yao said.

And Richardson’s mentors who have been clinical physicians and researchers from Clemson, have helped him excel in his research and applying for grants.

“Between SC-TRIMH and the support that Clemson offers for new investigators, I’ve been able to make connections with investigators here at Clemson but also investigators at MUSC and USC,” Richardson said. “These COBRE centers are exceptional at helping researchers make connections across the state and I wouldn’t have been able to get this far in my research if I didn’t have some of these connections.”

Through his short time at Clemson as a junior investigator, he’s collaborated with scientists and clinicians like Amy Bradshaw, Mike Zile, and Carol Feghali-Bostwick at the Medical University of South Carolina.

His research has been focused on tendon healing, and the same process from that research is part of his research for his R01 grant, which is focused on the heart. He and his research team are using the same tools that they’re working with in the orthopedic world but applying them to how the heart remodels itself.

“We are looking at collagen and healing after you have a heart attack and how that scar tissue forms and the way the body regulates itself,” Richardson said. “There are cells that make the collagen but then there are other cells that make proteases that eat away the collagen and then there are other cells that make protease inhibitors which are inhibitor molecules that inhibit the proteases that eat collagen. But it turns out that those molecules that are involved in the heart are the same molecules that are involved when you tear a tendon and are trying to heal a tendon.”

[vid origin=”youtube” vid_id=”MqRb5Ps-Erw” size=”medium” align=”left”]

In his lab, there are two main foci: experimental mechanobiology studies and computational models to predict healing rates.

“We build these little reactors & these little stretching devices for tissues and subject them to these mechanical forces,” Richardson said. “Every time a tendon or tissue moves, such as in a leg or a heartbeat, it’s deforming and moving and there are strains and stresses that are involved. Those mechanical forces change the biology of our tissues, so we study that in the lab.”

They also build computational models to translate those changes into equations and then use the computer models to make predictions about the human body and its healing processes.

His next steps for the SC-TRIMH tendon project will be to two-fold. First, he first plans to use the team’s computer models to identify particular drug therapies that should theoretically enhance tissue healing in tendons under low mechanical tension vs. other drug therapies that should enhance healing in tendons under high mechanical tension. Secondly, the team will use their mechanical bioreactors to experimentally test these model-identified therapies on real tendons.

“If successful, our findings could eventually help clinicians tailor specific therapies based on a given patient-specific context,” Richardson said.

While he continues to work on his SC-TRIMH research project, Richardson will also become a mentor for others as part of the SC-TRIMH initiative, Yao said.

“We look forward to his continued participation in our COBRE where he will serve as a role model and mentor to the other trainees and assist us in creating a critical mass of NIH investigators on campus,” Yao said.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu