Historic flooding, COVID-19 delays and the sun relentlessly beating down on the Nevada desert couldn’t keep Chenning Tong and his team from gathering data for their research.

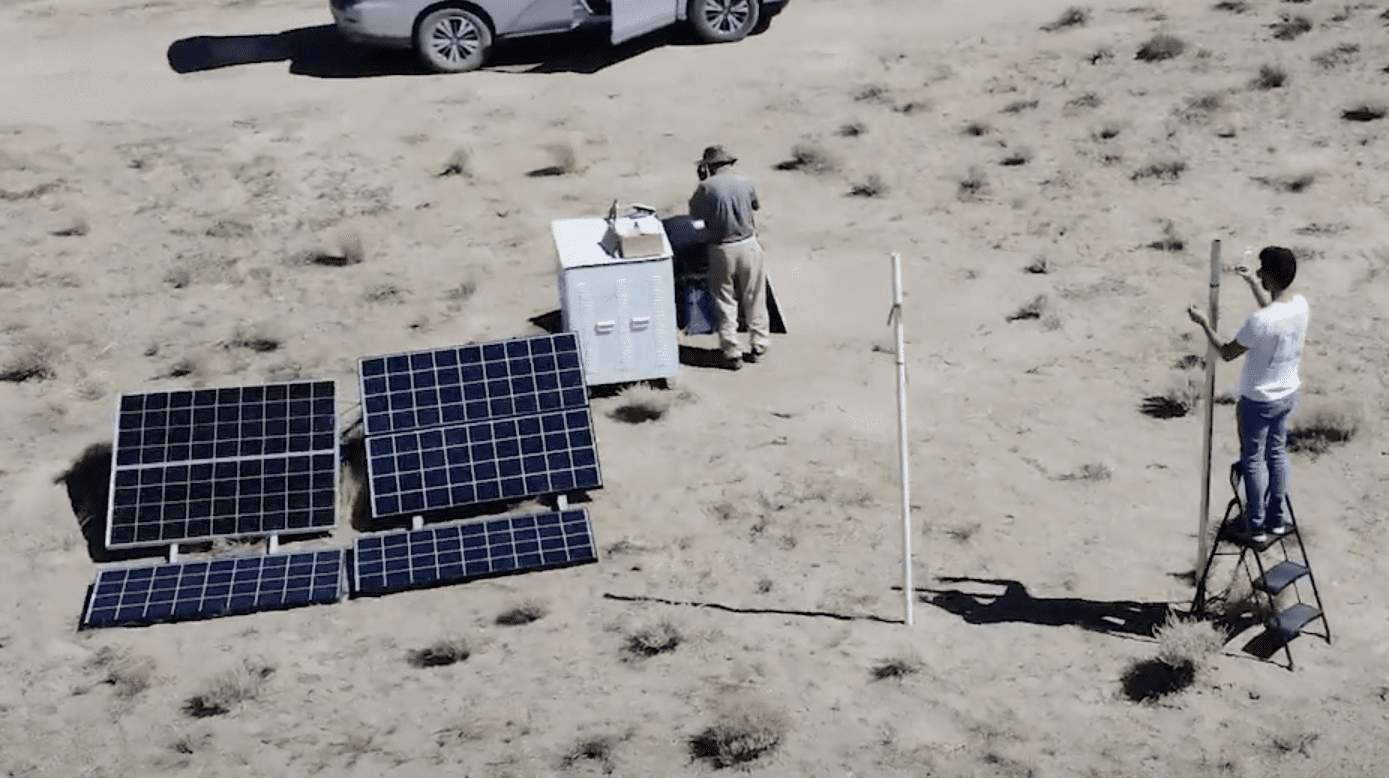

The Clemson University mechanical engineering professor led a team that set up sophisticated scientific equipment amid the sand and scrub brush of Tonopah, Nevada as part of research into long-standing questions about atmospheric turbulence.

In an age when an increasing amount of research is done on computers, the Tong team needed to do a critical part of its work the old-fashioned way– out in the field among the scorpions, coyotes and antelope, vulnerable to the whims of nature in the high desert.

“This was a big part of the project, and to some extent it was the riskiest part because something could have happened and we wouldn’t have been able to do it,” Tong said. “But we were able to do it, and we are very happy about this. The rest is up to us.”

The team gathered its data during the hottest part of the summer with temperatures often soaring into the upper 90s and occasionally into the triple digits.

The U.S. National Science Foundation National Center for Atmospheric Research (NSF NCAR) is in the final stages of data processing and quality control for most of the data collected. The Tong team expects to begin analyzing it soon.

The remoteness of the site was part of the challenge. It was between Las Vegas and Reno but more than three hours from either. The nearest hardware store was nearly two hours away, so a simple equipment run took the better part of a day.

But the Tonopah site had what the team needed for its study– an expansive plot of open land with consistent wind speeds and relatively little air traffic.

About 20 researchers from Clemson University, NSF NCAR and California State University, Chico converged on the remote location in early July 2023 to set up the equipment they needed.

NSF NCAR served as the primary provider and operator of the instrumentation used throughout the project. That included a network of instrumented towers, which included more than 50 sonic anemometers.

They were spaced about 5 meters apart, stretching for about 250 meters, which was “probably the largest deployment in the world,” Tong said. The anemometers used sound to measure wind velocity and direction in three dimensions just above the Earth’s surface.

Chris Roden, an electrical engineer with NSF NCAR’s Earth Observing System, said it was a pleasure to work with Tong.

“He is a great mind and is always thinking of new approaches,” Roden said. “He loves to ask a lot of questions about the world and the environment around us and then come up with ways to better understand it.”

One instrument on scene was exceptionally rare– the Raman-shifted Eye-safe Aerosol Lidar (REAL). It was brought by its inventor, Shane Mayor, a professor of Earth and environmental sciences at California State University, Chico.

The REAL is housed in two shipping containers on a trailer with a roof-top scanner. Researchers use the scanner to scan a laser beam horizontally about 5 meters above the ground.

With the REAL, researchers were able to detect small amounts of dust invisible to the naked eye. They applied algorithms to the images they collected and were able to calculate the vector flow field.

“You can see the wind over a several kilometer area, and then Chenning can use that information to test his theory,” Mayor said.

The goal of the research is to fundamentally revise the Monin-Obukhov similarity theory, which Tong said was successful when first proposed in 1954 but has since been found to have some major shortcomings.

Tong is calling his new theory the multi-point Monin-Obukhov similarity theory and said it is able to predict wind fluctuations and other properties of atmospheric turbulence that the original fails to predict.

The answers Tong and his team find could help lay the groundwork for advances in several areas ranging from wind energy and weather forecasting to air pollution control.

The team’s original plan was to conduct the research in 2022, but pandemic-related delays pushed back the project by a year.

The original location was supposed to be in California’s Central Valley, where the team had gathered data for a previous study. But heavy rain combined with historic mountain snowmelt flooded their study site, and the team had to find another spot.

Steven Oncley, who was then head of the integrated flux system for NSF NCAR, played a key role in helping find a new site under a tight deadline. It was April when the team learned it needed a new location, and Tong wanted to conduct the research in late summer and early fall for optimal conditions.

Oncley said that he, Tong, Mayor and other members of the team scoured Google Earth and asked colleagues for suitable locations. Later, Oncley, Tong, Mayor and Roden took a 1,000-mile road trip through the West to view the two most promising sites, the one in Tonopah and another in California.

Once they settled on the Tonopah site, Oncley used another set of his skills to keep the project moving forward. He serves on the Board of Trustees in Jamestown, Colorado (population 250) and said that he was able to use his knowledge and experience in small-town government to secure the necessary town and county approvals to conduct the Tonopah research.

It was a big effort in the lead-up to a final hurrah– Oncley retired after his role in the desert data-gathering was done.

“It went well,” he said. “This was a perfect example of the scientific method. Chenning had a clear hypothesis, he worked up a theory, published papers on that theory, checked it out with computer models where he could and was wanting to have some field data to check it out. That’s just exactly the way you want to have scientific inquiry done.”

Caleb Davis, a senior majoring in mechanical engineering, was among four undergraduates to join the team in the desert and solve some of the unique challenges that come with setting up precision equipment.

In later phases of the research, Davis helped launch weather balloons and flew a drone that measured such factors as pressure, temperature and wind speed. During time off, he had the chance to explore the area.

“I just loved the unique opportunity to be out in the middle of nowhere and getting to do the hands-on work,” Davis said. “You get to solve a problem and you get to make a process, see it through, make changes, and adjust.”

The project was made possible by a $2.2-million grant from the National Science Foundation. As the principal investigator, Tong was on site for the duration, leaving July 9 and returning to Clemson Sept. 24.

Even with the unique challenges the team faced, Tong said he never considered quitting.

“This is too important,” he said.