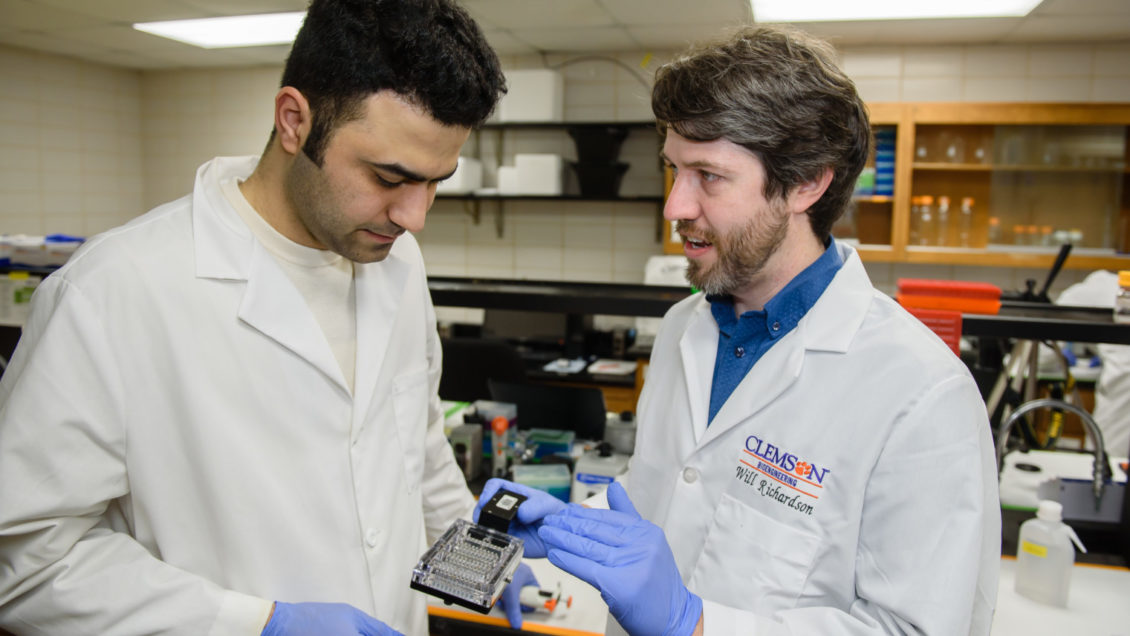

The millions of patients who suffer from a condition that contributes to heart failure could receive personalized risk assessments and treatments with the help of new research led by Will Richardson of Clemson University.

Richardson, an assistant professor of bioengineering, is receiving $1.9 million from the National Institutes of Health for five years of research focused on cardiac fibrosis. The condition occurs when material builds up in heart walls, hampering its ability to pump blood.

When cardiac fibrosis progresses to heart failure, it can prove deadly. As many as 60 percent of patients die within five years of developing heart failure, which afflicts 6.5 million Americans, Richardson said.

No drugs have been approved to treat cardiac fibrosis specifically, and doctors are often left with trial-and-error experimentation when treating patients who have it, he said.

For Richardson, the solution could start with math.

His team has taken what scientists already know about how molecules interact in the body, and turned that information into mathematical equations. Richardson envisions a day when measurements from a patient’s blood or tissue sample would be plugged into those equations.

“We want to have this computational tool where the clinician can come and say ‘this is your risk, and we’ve simulated these 10 or 100 or 1,000 different drug combinations and regimens,’” he said. “We’re never going to do trial and error for those many combinations, but a computer model can crank all those options overnight.

“The next day the cardiologist would say, ‘This is the optimized drug regimen or therapy for your particular levels.’”

The research is in its early stages, and it would take more than a decade of experimentation for any new tool to hit the market, Richardson said.

The central question that Richardson plans to address in his project is whether the mathematical model he has in place behaves as predicted and, if not, what ought to be changed. He plans to test the model with data gathered from heart failure patients at the Medical University of South Carolina.

“We can test what the model predicts because we already know in those patients whether or not they got better or worse, or what their prognosis was,” Richardson said. “We can test that against the model predictions to say, ‘Is our model making good predictions or bad predictions?’ And if it’s making bad predictions what part of the model is responsible for those bad decisions so we can come back and tweak that part of the model and improve it?”

Funding for the research comes through the National Institutes of Health’s R01 program. Martine LaBerge, chair of Clemson’s Department of Bioengineering, said the program is nationally competitive.

“Dr. Richardson is highly deserving of this grant,” she said. “He has assembled an excellent, multi-disciplinary team and brings to the project his expertise in cell stretching and computational modeling. He is well positioned for success.”

Richardson is principal investigator on the grant. Co-investigators from Clemson are Zhi Gao, Joseph Bible and Taufiquar Khan. Co-investigators from MUSC are Michael Zile, Amy Bradshaw and Catalin Baicu.

Anand Gramopadhye, dean of the College of Engineering, Computing and Applied Sciences, said Richardson and his team are in a position to advance health innovation, one of six innovation clusters identified in the ClemsonForward plan.

“I congratulate Dr. Richardson on his grant,” Gramopadhye said. “The amount of the award and the fact that it comes from the R01 program is a testament to its importance and the high value that his peers see in it.”

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu