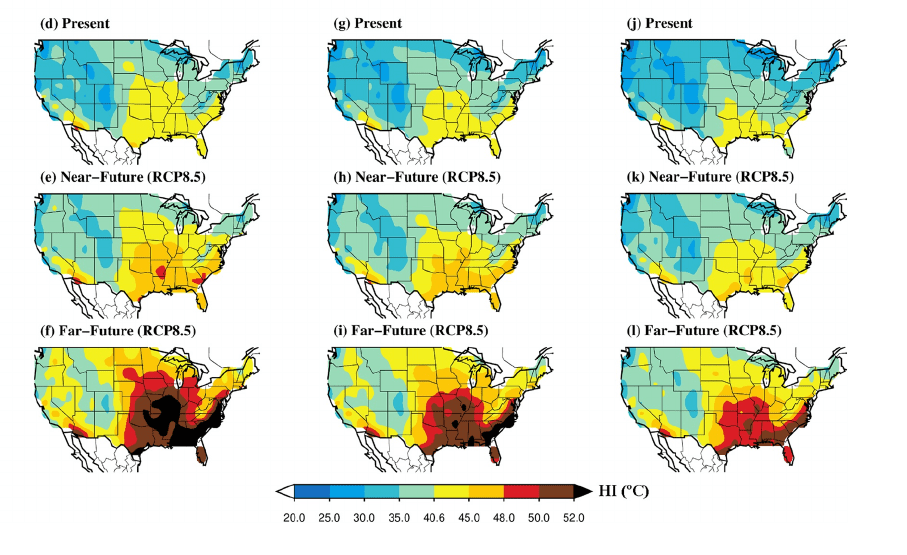

Periods of extreme heat in South Carolina will increase more than threefold by century’s end, making it one of the hardest hit in the Lower 48 states, if greenhouse gas emissions continue unabated, according to recent research in the journal Earth’s Future.

One of the co-authors, Ashok Mishra, an associate professor of civil engineering at Clemson University, warned that the European heat wave that claimed more than 70,000 lives in 2003 could become a frightening harbinger of what’s to come in the United States.

“We need a strategy to minimize the impact of these extreme events in the future,” Mishra said. “Stronger communication between policymakers, stakeholders and researchers could help us prepare and head off the worst of the impacts.”

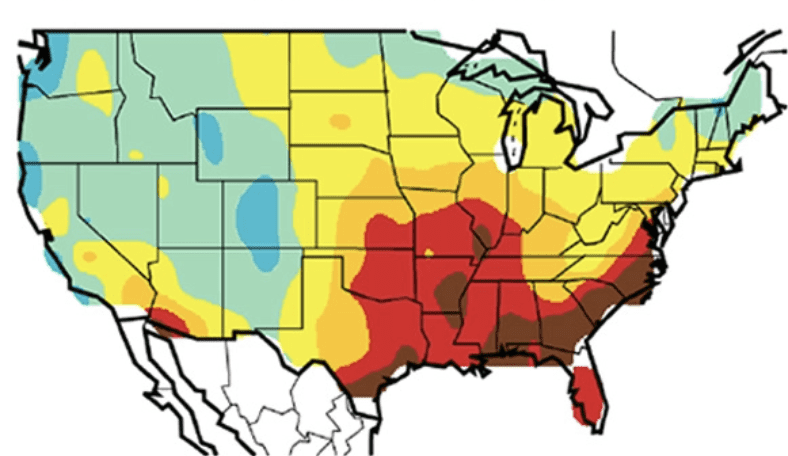

Researchers used the National Weather Service’s heat index to quantify heat stress severity. The heat index combines air temperature and relative humidity to give an idea of what the weather feels like to the human body.

Periods of extreme heat stress ranging from one to seven days would increase most in four densely populated regions, the study predicted. The Southeast Piedmont, which includes South Carolina, could expect a more-than threefold increase, along with the Northeast, Midwest and Desert Southwest, according to the study.

In an interview, Mishra said extreme heat would reduce crop yields, lead to more periods of drought and drive up demand for air conditioning, reducing the available energy supply.

Construction workers and others who labor outside would have to reduce the number of hours they work, resulting in billions of dollars in lost work time globally, Mishra said.

‘Accept that this is happening’

The research was the third climate change paper that Mishra has co-authored or helped co-author in a year. Sourav Mukherjee, now a postdoctoral fellow, served as a co-author on two of the papers.

“The first thing we need to do is accept that this is happening,” Mukherjee said. “Once we accept it, the next step should be to mitigate or reduce the impact.”

The Earth’s Future study sharpened the focus on heat stress, which occurs when temperature and humidity get too high for the human body to shed excess heat. Heat stress can cause health problems, such as stroke and heat cramps.

To gauge the overall risk of heat stress exposure, the research team considered projected population shifts, along with the expected effects of climate change, including frequency and severity of extreme temperature and humidity and which areas can expect the sharpest increases.

The idea was to give a view of which areas of the country will be hardest hit based on how many people will be living there and how much climate change drives up the heat index.

Combining the factors made the research unique because most previous studies have looked at them independently, Mishra said.

The team divided the Lower 48 states into a grid and came up with risk ratios for each area.

The risk ratio would increase more than three times in the northern Midwest, the coastal Pacific Northwest, central California and northern Utah, if greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced, according to the study. The Southeast Piedmont, northern Texas and portions of the Southwest could expect 2.5 times the current risk ratio, according to the study.

Biggest concern is flooding

Previous research by Mishra’s group projected how climate change could affect water supplies.

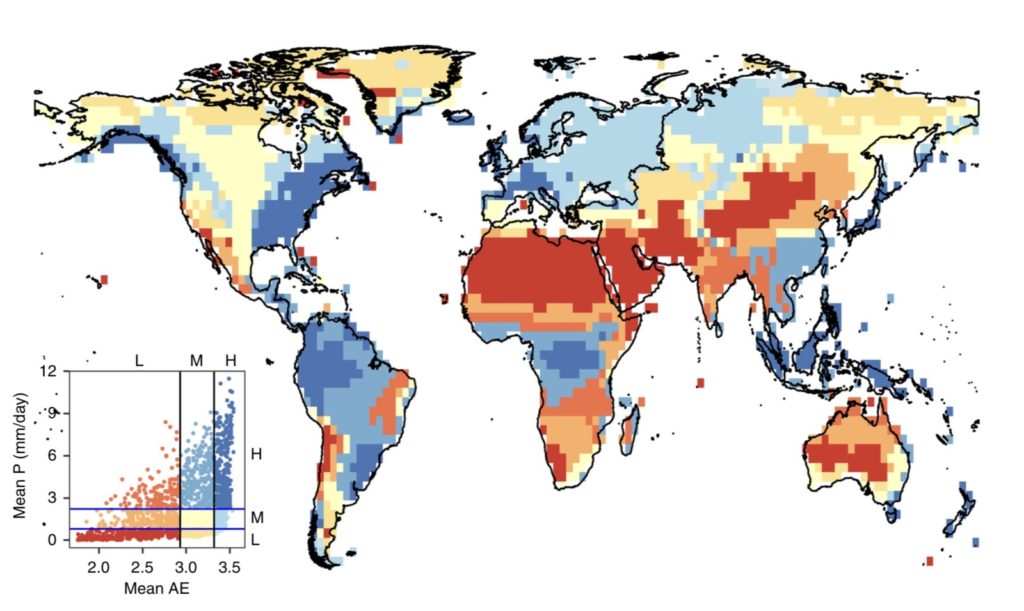

A study he and former Ph.D. student Goutam Konapala co-authored last year in the journal Nature Communications found the world can expect more rainfall as the climate changes, but it can also expect more water to evaporate.

The combination will complicate efforts to manage reservoirs and irrigate crops around the world as the population grows, Mishra said.

Most of the Eastern United States, including all of South Carolina, can expect greater precipitation and evaporation in both wet and dry seasons, and the amount of water available will vary more widely than it does now, according to the study.

The greatest concern will be more flooding, Mishra said.

The regions that will be hardest hit are the ones that already get slammed with rain during wet seasons and struggle with drought during dry seasons, according to the study. They include much of India and its neighbors to the east, including Bangladesh and Myanmar, along with an inland swath of Brazil, two sections running east-west across Africa, and northern Australia, according to the study.

“The regions which already have more drought and flooding relative to other regions will further see an increase in these events,” Mishra said.

Risks of heat and drought

In February this year, Mishra and Mukherjee co-authored a separate paper in the journal Geophysical Research Letters that found several regions around the world are experiencing heat and drought at the same time with increasing frequency, duration and severity. In the United States, the West was most affected.

Mishra and Mukherjee analyzed temperature and precipitation records from 1983 to 2016 for the paper. The key innovation was to look at daily and weekly data, rather than monthly data, as has been done in past research. The more granular analysis provides a better picture of risks associated with simultaneous heat and drought, they said.

The results of the analysis will aid forecasting efforts and help to improve hazard preparedness and mitigation strategies for the vulnerable regions of the globe, according to the study.

Jesus M. de la Garza, chair of the Glenn Department of Civil Engineering at Clemson, said the three studies contribute to a body of research that is helping the globe plan for a more sustainable future.

“With this knowledge, various stakeholders across the state, nation and globe will be better positioned to take action and prepare for future eventualities,” he said. “I congratulate Drs. Mishra and Mukherjee on the recognition they are receiving for their research. It is a testament to their hard work and the level of scholarship they bring to the department.”

To learn more, you can read the papers:

“Anthropogenic Warming and Population Growth May Double U.S. Heat Stress by the Late 21st Century,” was published in Earth’s Journal. Co-authors were Mukherjee, Mishra, Michael E. Mann and Colin Raymond.

“Climate change will affect global water availability through compounding changes in seasonal precipitation and evaporation” was published in Nature Communications. Co-authors were Konapala, Mishra, Yoshihide Wada and Mann.

“Increase in Compound Drought and Heatwaves in a Warming World” was published in Geophysical Research Letters. Co-authors were Mukherjee and Mishra.

Get in touch and we will connect you with the author or another expert.

Or email us at news@clemson.edu